Two steps forward [from the October MM&D print edition]

Share

Share

If there’s an overall theme to this year’s Annual Survey of the Canadian Supply Chain Professional, it’s “two steps forward, one step back”.

The survey, a more comprehensive version of the 20-plus-year-old Supply Chain Salary Survey, shows gains in some categories, but also indicates declines in others. Overall the picture it paints is one of a generally improving situation for supply chain professionals, just not completely rosy for everybody.

This year’s survey, which was conducted on behalf of three magazines—MM&D, PurchasingB2B, and CT&L, and sponsored by the Purchasing Management Association of Canada (PMAC)—was answered by 2,405 members of the Canadian supply chain community, the largest pool of respondents in the history of the survey.

The accuracy of the study is ±2 percent 19 times out of 20.

The figure everybody wants to know is the average supply chain salary. In 2012 it is $85,178.

In 2011 the average salary across Canada was $82,800. So in 2012 the mean climbed 2.9 percent, which is better than the 2.2 percent increase between 2010 (when the mean salary was $81,000) and 2011, but it’s still a far cry from the 3.7 percent jump between 2009 ($78,100) and 2010.

As is typical, there was as wide disparity between salaries across the country. Manitoba and Saskatchewan had the lowest average in 2012 at $75,190 while western neighbour Alberta paid the most at $101,448.

While Atlantic Canada is on the lower end of the salary scale, supply chain professionals there experienced the highest percentage of pay increase in the country. Jumping from $68,700 in 2011 to $75,781 in 2012 represents an increase of 10.3 percent. In comparison, their colleagues in British Columbia only saw their salaries grow by 1.4 percent.

Having a competitive salary is important to 97 percent of respondents, and it seems most people are relatively satisfied with how competitive their wages are. Nineteen percent reported they were very satisfied and 52 percent said they were somewhat satisfied. This is consistent with previous years’ results.

Most people are optimistic about future compensation. A total of 70 percent of respondents said they anticipate an increase in salary in 2014.

As expected, there was a wide spread in salaries between those at the top of the supply chain ladder and those on the lower rungs.

In 2012, those at the executive level reported a mean salary of $142,322 (compared with $140,000 in 2011). Those at the managerial and clerical levels, and those with professional status (engineers, for example) also saw slight increases (2.6 percent for managers, 3.3 percent for engineers, and 3.5 percent for clerks and administrators).

Those who classify their roles as supervisors, consultants, tactical/operations and “other” weren’t as lucky. Supervisors saw their salaries fall 0.4 percent from 2011 to 2012. Consultants experienced a 0.9 percent drop.

Operational and tactical personnel experienced a major loss, as their salaries came in 6.8 percent lower than the previous year, and those in the “other” category lost the most with a 10.6 percent decrease.

As much as it would be great to report the wage gap between men and women has closed, that’s still far from the case. Women are making significantly less than their male counterparts, and they aren’t getting raises at the same rate.

In 2012, men earned on average $91,181. Women averaged $75,033. That’s a difference of over $16,000. In 2011, the figures were $88,300 for men and

$74,600 for women—a difference of $13,700, so it appears the gender gap took a backward step this year. As to whether it will regress to 2010 levels(where men were making $22,300 more) remains to be seen.

Not only are women falling behind in total wages, they also lost ground when relative wage increases are considered. Between 2011 and 2012, women’s wages grew a measly 0.6 percent while men saw their mean salaries increase 3.2 percent. Admittedly, this came after a year when the trends were reversed—from 2010 to 2011 women gained 4.6 percent while men saw their salaries decline by 5.7 percent.

Although the amount of work experience can be considered a separate factor in calculating compensation, when sex is looked at through the lens of experience, the results are particularly revealing.

For those who have worked in the supply chain for five years or less, their mean salary is $55,926, with men earning $56,127 and women receiving $55,690. (These figures are all down from 2011 when the average was $64,900 with men getting $68,500 and women earning $60,600.)

Six to 10 years of experience is worth $69,404 on average. Women working that length of time earned $67,531, but men received $71,395 which is 17.4 percent more.

For 11 to 15 years, men were compensated with $83,614 while women earned 19.6 percent less at $69,905, with the combined average being $77,979.

In the 16 to 20 year category, the average was $90,756 with men worth $95,120 and women $82,762, a difference of $17,826. That’s only a 14.9 percent spread.

The greatest gulf between the experience of men and women comes into play for those who have worked in the supply chain for 26 years or longer. With this amount of work experience, women earn $88,352. Men earn $107,337.

That’s $18,985 less for the ladies than the gents, which gives this pairing a 21.5 percent difference. The overall mean salary for people with this amount of experience is $102,833.

As much talk as there is in the supply chain about doing whatever it takes to attract new talent, younger workers didn’t really see many gains in their wages. In fact workers under 25 lost a considerable amount this year. Their mean salaries dropped 7.4 percent from $48,600 in 2011 to $44,986.

Admittedly those figures come from a small sample (fewer than 50 respondents), but even looking at the rest of the data, it seems younger employees didn’t fare as well as their more senior co-workers.

Workers between 26 and 35 earned one percent more in 2012 than they did in 2011. Those who are 36 to 45 saw their salaries go up 2.6 percent. The next category up, those between 46 and 55, earned 1.7 percent more.

After the age of 56, people found their raises were higher. Those aged between 56 and 65 earned 5.2 percent more and those over 65 got a three percent bump.

When broken down by level of education, it seems most people made some gains in 2012, with a few notable exceptions.

Even though it may be counter-intuitive (especially in light of the age-related figures) high school graduates earned 8.4 percent more this year. Their mean salary was $79,261. People with trade school or technical diplomas got 7.8 percent more, which translates to $83,556. The small sample of CEGEP grads (less than 50 people) had an increase of 9.4 percent, bringing them to $73,672. Undergraduate university degrees were worth an additional 2.7 percent ($87,101) and MBAs received 2.2 percent more ($100,914).

People who attended college saw a decline of 2.5 percent in their salaries.

In 2011 they earned $82,800, while in 2012 they got $80,697. The small sample of people (less than 50 in each group) with PhDs and non-MBA masters degrees also earned less. Those with masters had their salaries drop 2.7 percent (they earned $93,500 in 2011 and $91,018 in 2012). A doctorate was worth significantly less—$100,875 in 2012 versus $117,500 in 2011, a 14.1 percent decline.

Having specific supply chain training definitely paid off in 2012. Those with the SCMP (formerly CPP) designation had a mean salary of $94,835 in 2012. In comparison, those without it earned $83,864. People working on getting the designation are likely looking for a payoff, as they currently earn $71,198.

Other certifications and designations that equated to higher salaries were certified purchasing manager/CPM ($116,350), professional logistician/PLOG ($109,283), professional certified in materials handling/PCMH ($106,300), and certified professional in supply management/CPSM ($102,964).

The survey indicates most businesses will pay for upgrading. This year, 78 percent of survey respondents said their companies paid for education courses.

Sixty-nine percent work for organizations that paid for memberships in professional organizations and 63 percent had employers pay for professional certification programs.

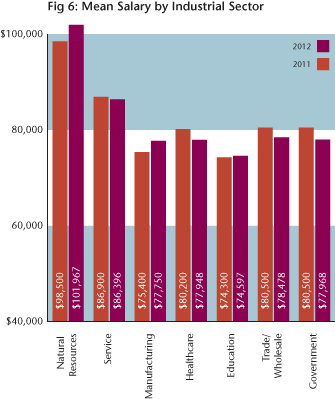

Supply chain professionals working in natural resources industries earned head-and-shoulders more than their colleagues in other industry sectors. In 2012, the mean salary in that vertical was $101,967.

There was a big jump down to the second place industry. The service sector paid supply chain professionals $86,396, compared with $86,900 in 2011.

Those in the trade or wholesale sector earned $78,478 (down from $80,500 in 2011). Government salaries were $77,968 (compared with $80,500 last year).

Health care workers saw $77,948 (a decrease from $80,200). Those in the manufacturing sector got $77,750 and people in education had a mean salary of $74,597.

Fortunately, almost all of the respondents have work. When asked if they are employed full-time in the supply chain, 96 percent of respondents who were PMAC members said they were, as did 94 percent of non-PMAC members. Two percent of people said they were looking for work in the supply chain.

The reasons why people are out of the supply chain were varied. Most (26 percent in total—31 percent of PMAC job hunters and 16 percent of non-PMAC job seekers) said they had been laid off. Nine percent said the company went out of business. Eleven percent answered they were forced to move into a non-supply chain role in their companies and seven percent in total chose other fields in their current companies. Seventeen percent reported they chose to leave their former organizations and hence the supply chain.

It seems respondents feel slightly more optimistic about job prospects in 2012 compared with last year. Overall, 69 percent said there were more jobs in the supply chain compared with five years ago. In 2011 67 percent thought there were more jobs.

It’s possible people’s perspectives about the job market have been influenced by the efforts of headhunters. This year 31 percent (34 percent PMAC and 27 percent non-PMAC) of people said they had been contacted by a headhunter more often than in past years. Eighteen percent reported less contact and 50 percent said they hadn’t noticed a difference.

Not only were most of the respondents employed, the majority expect to remain so for the foreseeable future. In responding to a question asking people where they saw themselves in two years, the vast majority—78 percent—said they expected to be in the same job or be promoted within the organization.

Environmental concerns are becoming more important to Canadian businesses.

Two-thirds of respondents said their companies have an environmental management plan in place and 55 percent said their company issues reports on environmental performance.

However, 60 percent said they do not have a formal supply chain management policy for environmental sustainability.

A majority of respondents are satisfied with the sustainability practices of their companies. Seventeen percent said they were very satisfied, and 59 percent are somewhat satisfied. Nineteen percent said they were not very satisfied and four percent are completely unsatisfied.

Although 24 percent of respondents said they experienced no changes in the nature of the job, most people did report some type of change. On the positive side, 36 percent said they received a raise, 25 percent said they earned a bonus and 12 percent were promoted. In contrast, 23 percent reported their salaries and job titles remained the same, but they now had to shoulder more responsibility due to cutbacks in staff.

The most pressing issue on the mind of supply chain professionals in Canada during the past year was cost control. Thirty-two percent of respondents put it on top of the list of issues they’ve been forced to face in the last year. Other concerns were supplier risk management (eight percent), capacity shortages (eight percent), reorganizations (eight percent), risk management (seven percent), and forecasting (six percent).

Cost control also tops the list of expected issues for the next twelve months, as 32 percent again said they expect that to be their most important issue. Reorganization and capacity shortages were both listed by eight percent of respondents as their most expected issue, and seven percent picked supplier risk management and risk management as their top choices.

Forecasting was the top pick of six percent of respondents.

While much of their job is spent worrying about what’s going on outside the walls of an organization, Canadian supply chain professionals need to pay attention to what’s happening inside their companies as well. A total of 95 percent of respondents said it was important to be able to influence their jobs, but only 70 percent indicated they were satisfied with their level of influence (24 percent were very satisfied and 55 percent were somewhat satisfied). In a related question, 86 percent were satisfied with the relationship they have with their supervisors, bosses and superiors.

Although there may be pressing concerns in the supply chain, it seems respondents try not to let the problems and issues overwhelm them.

Maintaining a healthy work/life balance seems to be a key priority, as 70 percent of respondents said it was very important and 25 percent called it somewhat important.

As to whether they’re successful in the balancing act, 30 percent say they are very satisfied with their work/life balance and 52 percent say they’re somewhat satisfied.

All of these figures are very similar to the responses generated in 2010, although going back to 2008, it does seem there is a slight downward trend over the years.

Most people are relatively happy doing what they’re doing. A total of 31 percent of respondents said they’re completely satisfied with their jobs; 56 percent said they’re somewhat satisfied; 10 percent report being not very satisfied and two percent are completely unsatisfied.

The people who answered the survey seem to work in places that value the supply chain and the people who work in it. Seventy-seven percent of people surveyed said their company realizes business wouldn’t function without the supply chain (only 17 percent disagreed with that statement) and 71 percent reported their influence has increased within their organization.

Those who replied gave a wide variety of answers when asked how they increased their influence. Among the responses were monetary savings and cost reductions (17 percent), strengthened communications (10 percent), improved order processes (eight percent), and increased contact with senior management (five percent).

Leave a Reply